Turning onto the paved road from my driveway, I wasn't

surprised to see a dead armadillo. In Florida, armadillos are one of the most

common victims of highway mortality.

I didn't think about the dead armadillo again until I was on

my way home and noticed a contingent of vultures surrounding the road kill. I

pulled over for a better look, which of course caused the wake — that's the

name for a group of feeding vultures — temporarily to disperse.

What I saw was almost nothing.

The animal's tough armored skin, long tail and clawed feet

remained, but its innards — all soft, edible parts — were completely gone. In

less than three hours, the vultures had not only scored a meal but also cleaned

up what would have become an unsightly, smelly mess.

Most of us don't think of vultures as emissaries of aid but,

really, that's what they are. These large, less-than-pretty birds are nature's

clean-up crew keeping our roads, yards and public spaces free from animal

remains. Vultures transform stinky decaying matter into life-sustaining

nourishment. If that doesn't earn them our thankful appreciation, I don't know

what will.

.JPG) |

| Vultures feed upon a wide range of recently killed animals |

As I stared at the empty shell of what had only hours ago

been an active warm-blooded mammal, I was impressed by nature's efficiency. In

addition to vultures, numerous flies buzzed about, busy with their own form of

carcass decomposition.

Most people wouldn't give such a situation much thought.

After all, neither vultures nor armadillos are beloved animals. Armadillos are

despised because they dig holes in yards and burrow under structures. And

vultures? Well, they're ugly and eat carrion. What good are animals like these?

.JPG) |

| Armadillos aren't the most popular animals |

The answer is, "very good." Despite the fact that

their beneficial acts generally go unnoticed and unappreciated, the work both

animals do make the world a better place for human inhabitants.

The pesky armadillo rooting through the Saint Augustine

grass isn't digging up lawn divots just to annoy people or for sport. It's

foraging for food. The comical looking, nearly blind armadillo picks up the

scent of ants, termites, beetles and lawn-damaging grubs, devouring them with a

voracious appetite.

Armadillos keep the insect world in check in much the same

way the ungainly vulture keeps decomposing matter under control. Both animals

help people by doing the dirty work of everyday life.

Wouldn't it be nice if people were as diligent at cleaning

up their messes as the animals we dismiss so casually?

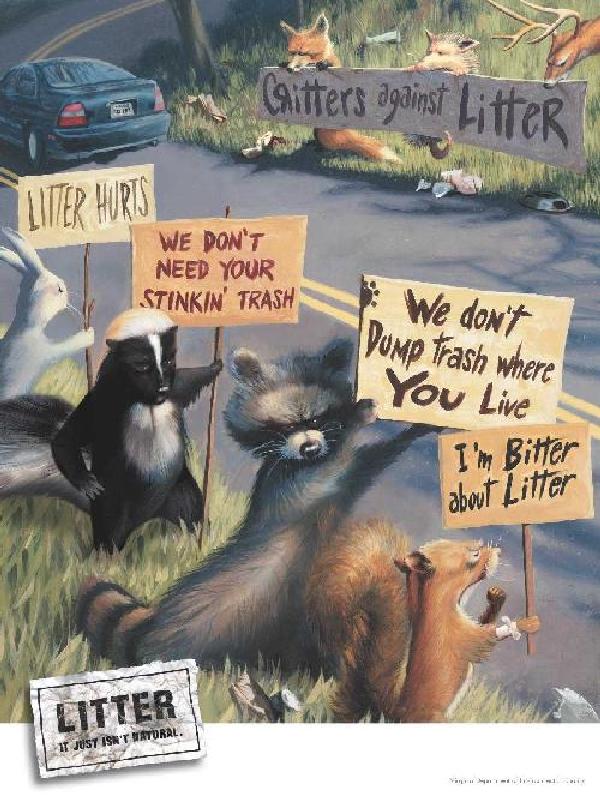

Piles of litter mar the landscape along the same stretch of

county-maintained road where the bald-headed birds feasted on the unfortunate

armadillo. Remnants of meals carelessly tossed from car windows have come to

rest alongside used tires and construction detritus. Reminders of human

indifference dot the roadside like pocks on nature's face.

|

It took less than three hours for vultures to eliminate most

evidence of the armadillo's existence, but the litter along my quiet country

lane will remain indefinitely unless some Samaritan decides to take the time to

pick up the trash.

The process of carnage-hungry critters consuming a dead

animal is a marvel of the natural world, while tossed-aside trash along the roadside

merely exemplifies the blatant disconnect some people have from any life but

their own. It demonstrates disrespect and ignorance, along with a lack of

compassion and connectivity.

Vultures may be ugly, but humans can be stupid. We're also

not very good at cleaning up our own messes.

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment